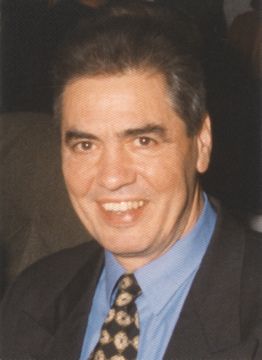

Interview with Ernst Stickel

Innovations and in-house inventions have made BSH what it is today: a successful international company. When it comes to revolutionary innovations in the area of dishwasher technology, one name in stands out in particular at BSH: Ernst Stickel, long-serving designer and employee.

BSH Wiki: Mr. Stickel, you completed your training with Bosch. How would you describe your initial working years?

Ernst Stickel: I started off as a mechanic in tool manufacture, but felt somewhat under-challenged. Bosch was offering draftsman training at this time, which I ultimately completed, but I once again found myself dissatisfied (laughs). I therefore decided to attend technical college. I went on from there to design special machines, but soon realized that I had to train many young engineers along the way. Unfortunately, I didn’t graduate from high school, which meant that I hadn’t really thought about studying engineering. Finally, I was given the opportunity to take part in a pre-semester as the fourth-best Baden-Württemberg apprentice. That’s what I then did and completed the course in precision engineering at Ulm Technical University. I was hired again in 1965 as a designer for dishwashers. I am grateful to Bosch for repeatedly re-hiring and supporting me.

BSH Wiki: Your drive to improve continuously is also reflected in your designs. AquaStop, for example, was a groundbreaking innovation. How did it come about?

Ernst Stickel: In the past, washing machines and dishwashers could only be operated under supervision, and the faucet had to be turned off after use. While this may have been clearly stated in legal terms, nobody ever did it (laughs), so accidents and resulting water damage happened all the time. The pivotal moment was an incident with a director of a ball bearing factory in Schweinfurt, when the water level in his apartment rose to 10 cm above his precious carpets.

BSH Wiki: AquaStop reliably protects against water damage. How does it work and what are its distinguishing features?

Ernst Stickel: We didn’t tell the customer how it works, but rather what damage it prevents and how convenient it is. Nevertheless, it’s a very simple concept. A second inlet valve is connected to the faucet and sleeving is pushed over the inlet hose. If there’s a leak in the inlet hose, the water is guided to the appliance's base tray and an electrical signal is sent to the inlet valve, which closes immediately. In addition, the float switch in the base tray then switches on the lye pump. The device has always worked with 100% reliability, as was confirmed by TÜV and the testing bodies on behalf of the insurance industry.

BSH Wiki: Innovations such as this surely take off quickly?

Ernst Stickel: Unfortunately, it’s not always that fast. There was much discussion initially as to whether AquaStop was too expensive or could give the impression that our products are faulty. However, Helmut Plettner, the then Chairman of the Board, ensured that the project was right at the top of the priority list. AquaStop was ultimately a complete success and all competitors were also very quick to acquire a license from us.

BSH Wiki: New ideas naturally often break with longstanding traditions.

Ernst Stickel: Another example is the 45 cm dishwasher. The width of 45 cm, which emerged as the desired width based on a survey of singles and employees from two-person households, was not included in the AMK (Modern Kitchen Working Group) standard. As a result, installation in customary kitchens was initially difficult. However, we quickly found a solution, and there were no protests from the kitchen furniture industry either. Thanks to the introduction of the 45 cm dishwasher, sales of small kitchens even increased on previous figures. Ultimately, this innovation was also a major success for us and we were struggling to keep up with delivery of all the orders.

BSH-Wiki: War die neue Breite nicht auch eine Herausforderung für die Konstruktion? Der schmalere Geschirrspüler leistet ja dasselbe wie der Spüler mit dem Standardmaß.

Ernst Stickel: Der neue 45er Spüler war besonders innovativ. So war es in der Tat eine Herausforderung, alle erforderlichen Bauelemente, beispielsweise auch einen neuen Wärmetauscher, in einem 15 cm schmaleren Spüler unterzubringen. Die entscheidende Anregung kam aus einer ganz anderen Branche: Mir fielen bei der Hannover Messe 1984 die LKWs auf, deren Motoren durch die aufgeklappten Führerhäuser zugänglich waren. Diese Technik wendeten wir auch beim 45er Spüler an. Wir nahmen eine Art Bierkiste und befüllten deren einzelne Fächer mit den entsprechenden Bauelementen. Dann montierten wir den Behälter mit einem Scharnier auf der einen Seite und klappten ihn, ähnlich wie das Führerhaus, zu, wodurch die Bauteile festgeklemmt wurden. So benötigten wir weniger Befestigungsteile und Schrauben, sparten Montagekosten und integrierten Innovationen wie den Durchlauferhitzer und den AquaStop.

BSH-Wiki: Waren alle Projekte von Erfolg gekrönt oder hatten Sie auch Reinfälle?

Ernst Stickel: Es gab zwar die eine oder andere technische Lösung, die ich heute anders machen würde, doch richtige Flops hatten wir nicht.

BSH-Wiki: Herr Stickel, gegen Ende wollen wir noch einmal auf Sie persönlich zurückkommen. Gibt es einen Moment in ihrem Berufsleben, an den Sie sich besonders gerne zurückerinnern?

Ernst Stickel: Da gibt es eigentlich zwei Momente: Zum einen die Verleihung des Innovationspreises der britischen Fachzeitschrift ERT in London 1988 für den neuen 45-cm-Geschirrspüler von Bosch. Zum anderen die Verleihung des Umweltpreises 1998 von der damaligen Umweltministerin Angela Merkel. Diesen Preis erhielten wir für unsere GV 630- Geschirrspüler, die für die damalige Zeit sehr effizient arbeiteten, Ressourcen schonten und in ein ganzheitliches Recyclingmodell eingebunden waren.