BSH induction cooktops

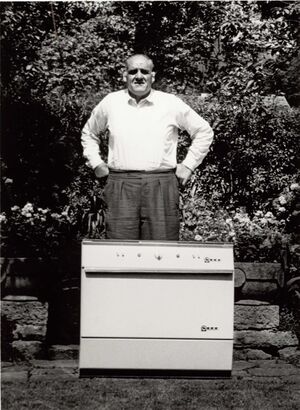

"Shoe size 56!" was the caption on the photo of the strongest man from the Black Forest. In the picture with him was the strongest new development on the home appliance market: the first European induction stove, produced in 1958 by NEFF in Bretten.[1]

Yet even the strongest man from the Black Forest proved to be powerless in attempting to convince consumers of the cutting-edge technology. It was only at the turn of the millennium that induction began to establish itself on the market. BSH[2] played a crucial role in shaping this development with a Competence Center for Induction Development and became one of the leading providers of this technology.

The long route to the consumer

The first patents for induction cooktops were registered in the U.S. at the beginning of the 1900s, with the first commercial models being exhibited at Chicago World's Fair in 1933. The front runner in Europe at the time was the cooker manufacturer NEFF.[3]

The induction cooktop operates according to the principle of a coil beneath the cooking area through which high frequency current flows, thus generating an alternating magnetic field. This alternating field is transferred to the base of the cookware by an insulating cold plate (generally ceramic class nowadays) and converted there to heat on the basis of induced eddy currents and remagnetizing losses. The cookware must consist of a ferromagnetic alloy for this purpose. High temperatures can thus be reached quickly. The cooktop only remains hot as long as there is contact with the cookware. The risk of burning, as was the case with conventional electric or gas cooktops, is thus minimized.[4]

The technology was not well received by consumers, however, until the latter part of the 20th century. The high purchase price – for the cooktop and additionally for special cookware made from ferromagnetic material – had a negative impact on marketing.

While the technology was only able to make its breakthrough slowly in the home appliance sector, it quickly gained momentum in other areas. By 1933 at the latest, Siemens began constructing induction ovens for smelting metals, while NASA and the U.S. military used the most diverse applications of the technology primarily in the field of aerospace.[5]

Expertise, innovation, induction

When BSH took over the Spanish company Balay in 1989, it acquired a specialist in the area of induction. Balay had already had an induction department at its site in Montañana for a number of years and had presented the first prototypes at the international trade fair in Cologne some two years prior to the takeover. Balay became the location for the Competence Center for Induction Development at BSH. At the same time, a contractually regulated collaboration with the electrical engineering and communication departments at the University of Zaragoza allowed enormous innovation potential to be tapped.

The enhanced development of the technology often led along unexpected paths. The license for manufacturing especially high-performance semi-conductors, or Mosfets as they are called, had to be purchased, for example, from the U.S. military. Engineer José Ramón Garcia recalled: "Without that license we would almost certainly not be the leading provider that we are today (....) on the global market."[6]

Series production commenced in 1990 in Montañana, with the breakthrough coming in 1999. Production increased 15-fold between 1999 and 2001. The new subject "Electronics in Induction" was established at the University of Saragossa in 2001, with BSH providing the teaching staff and the financial resources. Just four years later, BSH received its own Chair for Innovation.[7]

The induction division was expanded following the commercial breakthrough, with 48 patents for induction topics already registered in 2010, such as full-surface induction. Around 100 employees worked in the Competence Center's six labs and around half a million induction cooktops were being produced and exported to 78 countries worldwide. By 2016, production figures had more than doubled, with 1.2 million induction cooktops now leaving the BSH plants.

Notes

- ↑ BSH Corporate Archives, C04-0206, 1958.

- ↑ BSH was founded in 1967 as Bosch-Siemens Hausgeräte GmbH - BSHG for short. In 1998, the name was changed to BSH Bosch und Siemens Hausgeräte GmbH, with the short form BSH. Since the sale of the Siemens shares in BSH to Robert Bosch GmbH the company’s name is now BSH Hausgeräte GmbH, but still BSH for short.

- ↑ Badras, Catherine: Bedienungsanleitungen im Wandel. Eine explorative Studie über vier Jahrzehnte am Beispiel von Bedienungsanleitungen elektrischer Herde der Firma Neff. Berlin, Technical University, Diss., 2003, page 13. See also: BSH Corporate Archives, A05-0025, inform 01/2002 Jg. 25, page 15.

- ↑ BSH Corporate Archives, C04-0206, Press Release BPD 24-3273/0295.

- ↑ Theoretische und experimentelle Untersuchungen über den kernlosen Induktionsofen. In: Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen des Siemens Konzerns, 12 (1933), pages 1–4.

- ↑ BSH Corporate Archives, A05-0034, inform 01/2011 Jg. 34, page 20.

- ↑ BSH Corporate Archives, A05-0024, inform August/2001 Jg. 24, page 25. BSH Corporate Archives, A05-0034, inform 01/2011 Jg. 34, page 23.